We’ve previously been of the view that UK labour market statistics (as flawed as the ONS’s current output in this area is) offer some of the best insight into the future of UK demand for postgraduate taught study, at least on a macro level.

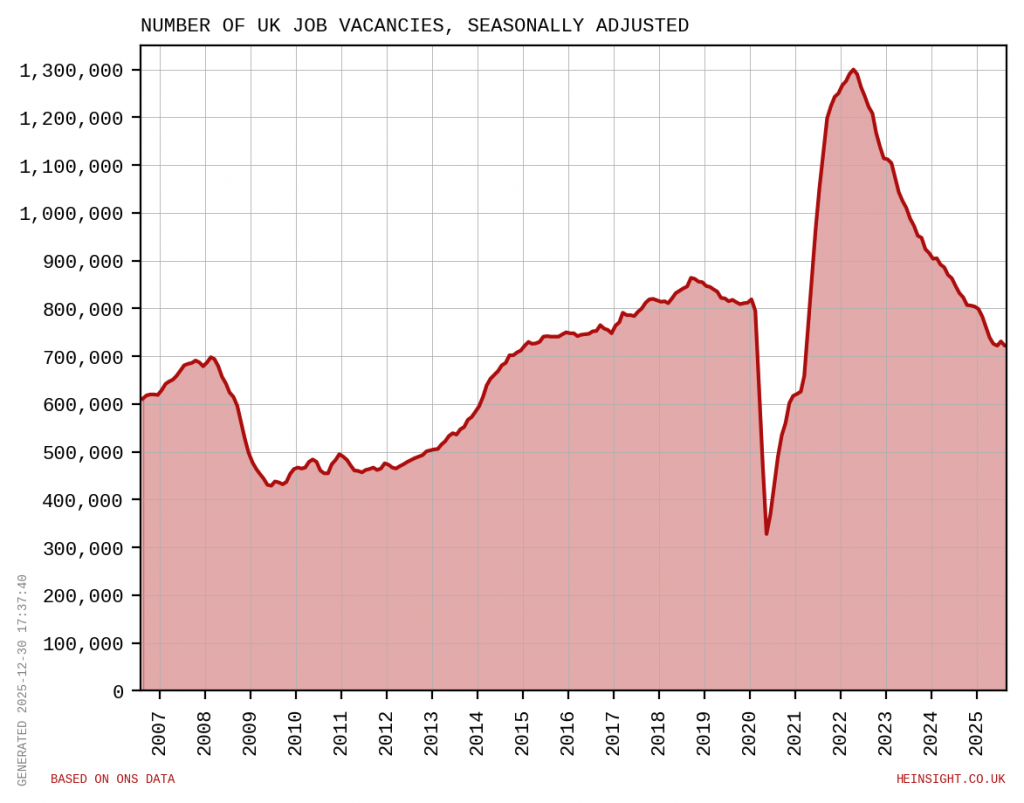

Overall UK PGT demand has previously closely followed labour market conditions, with a big rise in applications and enrolments in the early stage of the pandemic as job vacancies dramatically fell, employees were furloughed and anxiety about employment security increase. Demand from UK applicants then fell back as labour market conditions reversed from 2021 onwards, with high vacancies and strong pay growth reducing the incentives for PGT study. The theory here has been that if you’re already confident in your future career and earning prospects, you’re less likely to step away from this career to spend time and money on further study.

There are however signs that this relationship is now breaking down – excessive labour market tightness has now completely fallen away, with vacancies lower than in the years prior to the pandemic. Data on individual institutions’ UK PGT performance is hard to come by and sector level data only available with a long lag but there’s little to suggest that many are seeing a buoyant market with bumper recruitment.

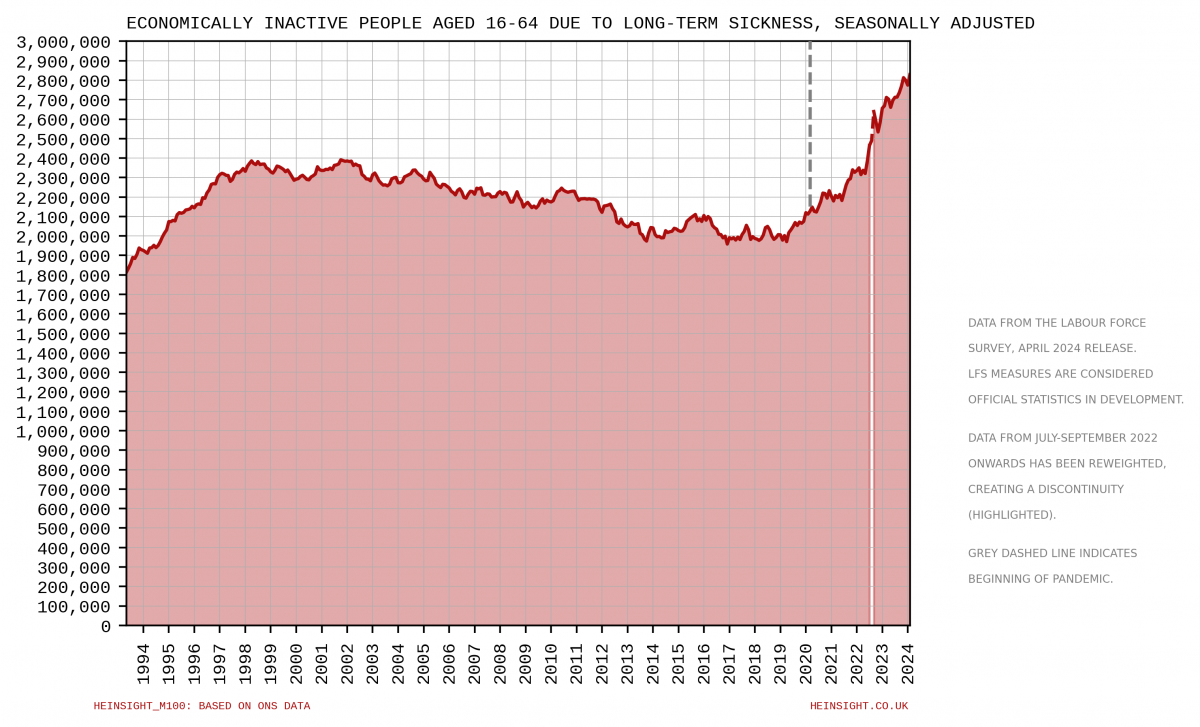

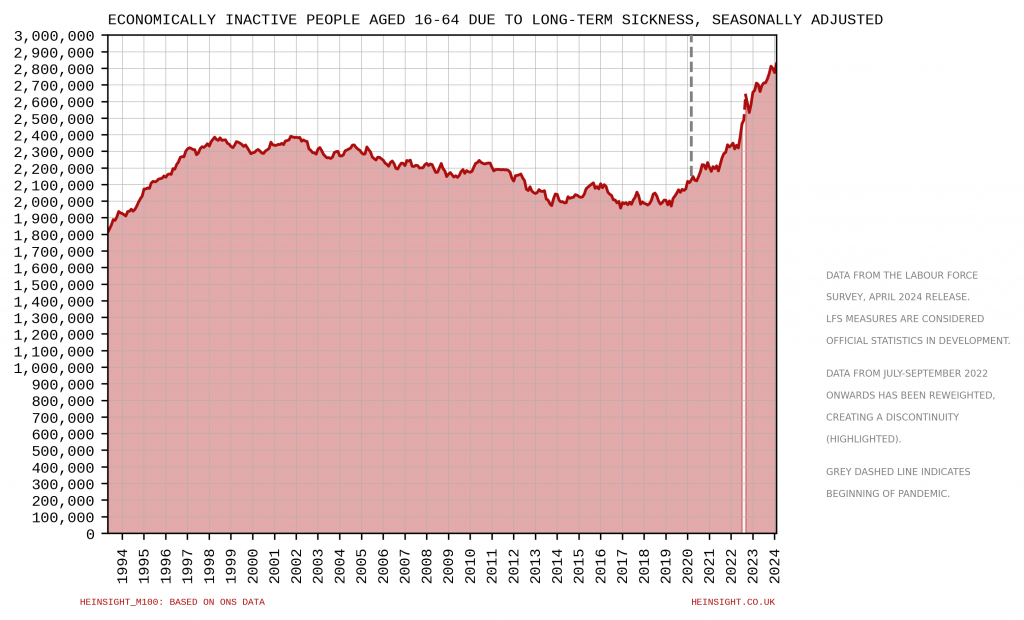

It’s likely that this change has come about because another determinant of UK PGT demand – affordability – has become the more important obstacle for prospective applicants. Put simply, it’s likely that many more people in the UK now consider PGT study a worthwhile investment in themselves than a few years ago, but their ability to fund this investment has meanwhile fallen.