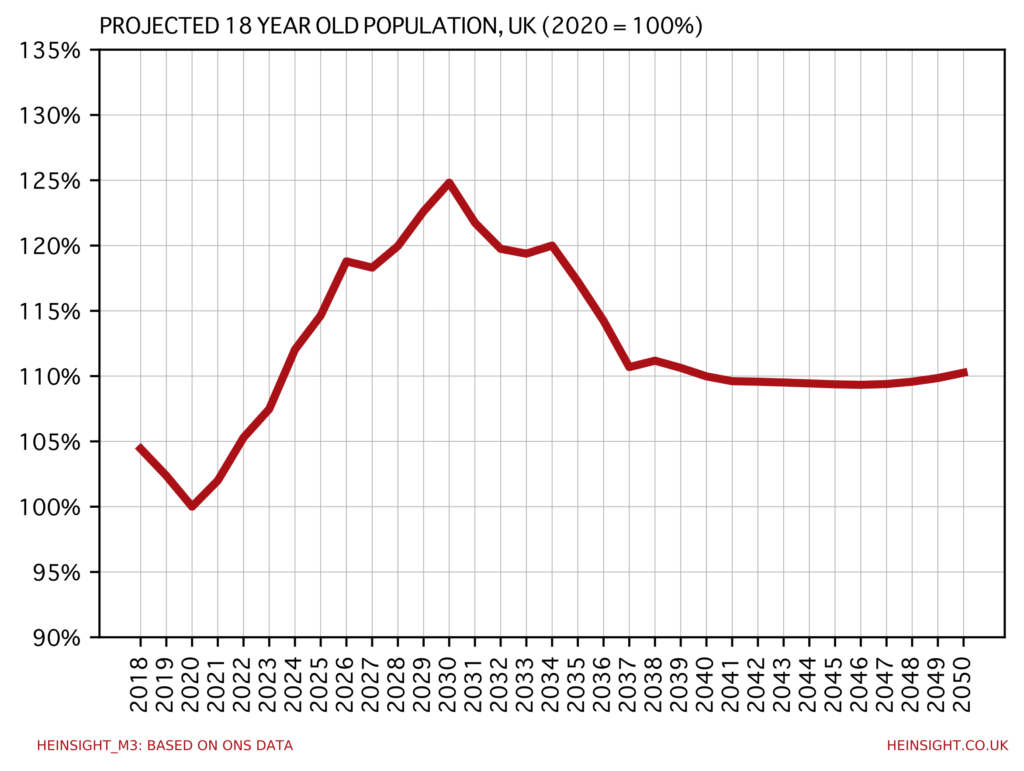

Those involved in recruitment, admissions or planning within UK higher education will be well aware of the ‘demographic dip’ – that the national population of 18 year olds has been declining since its peak in 2009. This trend has in many regards been obscured by rising HE entry rates, particularly since the lifting of student number controls, and stellar growth rates at some institutions will have made it all but invisible for some. With year-on-year falls in the number of school leavers picking up pace since 2017 demographics have however recently exerted significant pressure on some providers (the consequences of 2020’s A Level u-turn notwithstanding).

With the trend projected to have bottomed out in 2020, demographics is now beginning to become a story of growth once more. In fact the rate of growth will be greater than the previously experienced rates of decline, such that by 2024 the UK’s 18 year olds will again be as numerous as they were in their 2009 peak. Growth won’t stop there though and is projected to push on to set a new peak in 2030.

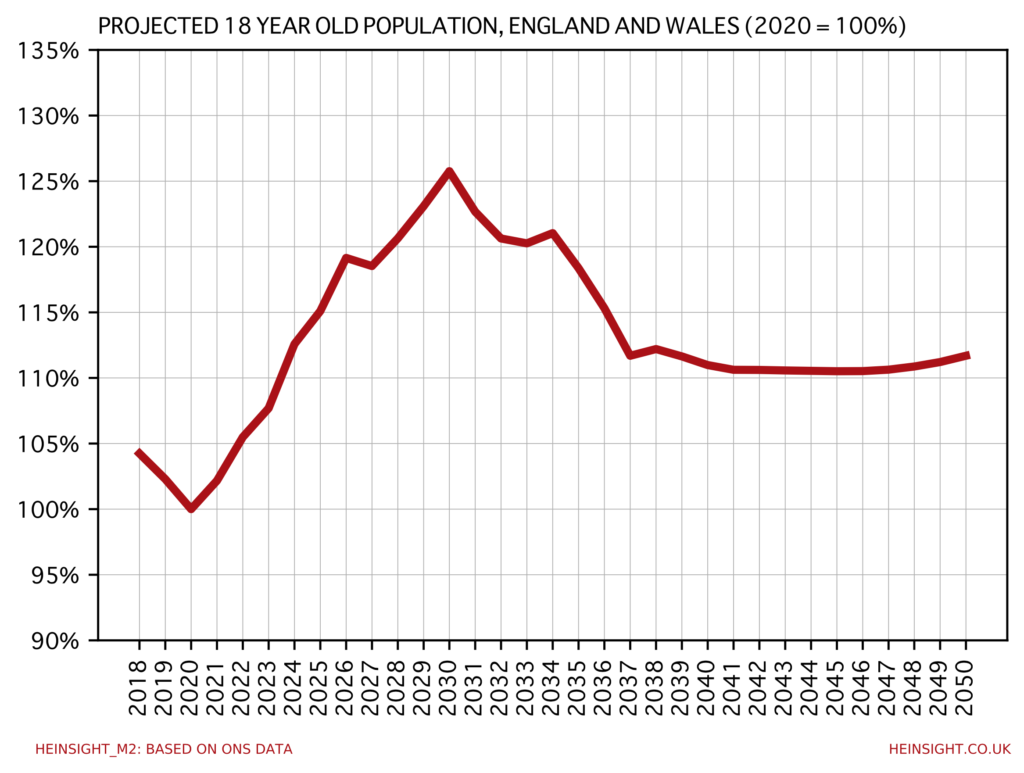

Notably England and Wales, the UK nations with the least remaining student number controls/funding cap mechanisms, are projected to experience ever so slightly higher growth than the UK as a whole.

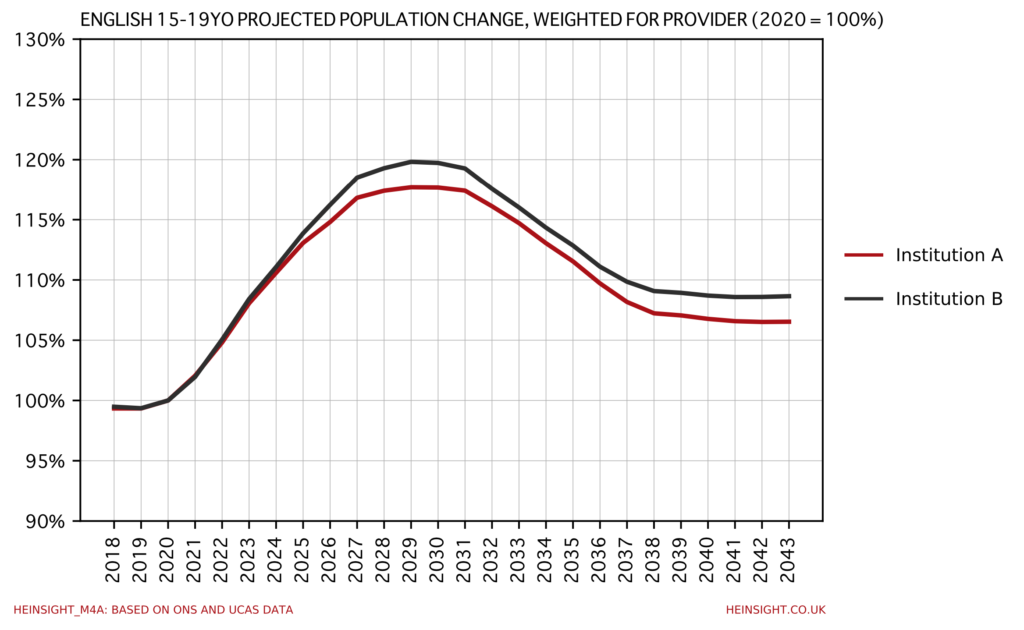

As well as an unequal distribution of growth between UK nations, growth within England will also be unequally distributed between its regions. Institutions will therefore experience the demographic surge to different degrees according to the representation of regions in their recruitment. Those that recruit highly locally or highly unevenly across England are likely to experience a trend significantly different to that which an unadjusted UK-wide view would have them expect.

The Office for National Statistics’ population projections broken down by English region only report by age groups (rather than individual ages, as in higher-level projections) but we can re-weight the change in the 15-19 year old group according to the weighting of each region in an institution’s 2020 application pool using UCAS end of cycle data. This exercise allows us estimate the increase in English demand an institution is likely to experience and it reveals some significant differences.

Below I’ve plotted the projected experience of two institutions: Institution A is a University in Yorkshire and the Humber whilst institution B is a University in the South West. Whilst they track very closely for the next few years, Institution A tops out at several percentage points lower than its southern counterpart and this gap persists as we reenter decline and eventually stabilisation. Note the more rounded trend here reflects the broader age group.

All regions are projected to experience some growth and the trend is therefore a positive one for all institutions. Whilst this will be welcome for those who have been facing recruitment difficulties in recent years it shouldn’t be missed that the demographic surge will have wide reaching consequences. Much of the sector is already well-advanced in plans to meet the capacity challenge but with high-tariff institutions having already exploded in size in the past five years many will inevitably have to reimpose harsher selectivity and risk progress in widening participation unless there are meaningful changes in UK HE admissions.

HEPs can and should be making greater use of demographic data to inform student number planning and that means going further than simply looking at national projections. Planners need to know how many of the soon to be much larger group of school leavers will be knocking on their doors and that requires modelling matched to the characteristics of their applicant base. Bringing unequal HE entry rates into the mix only makes this work more crucial for providers reliant on regionally-specific recruitment.